- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty

- Staff

- Alumni

- Others

Exploring community policing in Northern Ireland

In the late 1960s, long-simmering tensions between unionists and nationalists in Northern Ireland erupted into decades of violence known as the Troubles, a period during which more than 3,500 people died and 50,000 others were injured.

Stephen White, a former assistant chief constable at the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and Police Service of Northern Ireland, witnessed that unrest on the front lines as part of a police force that was tasked with finding answers for constant violence and threats of terrorism.

Recently, White – who was appointed by the Department of Justice as the new chairperson of the Royal Ulster Constabulary George Cross Foundation in 2018 – visited the University of Guelph-Humber as a guest of the Alpha Phi Sigma society to share with a group of largely Justice Studies students how the Police Service of Northern Ireland eventually reformed itself to better confront violence and to repair its relationship to the community.

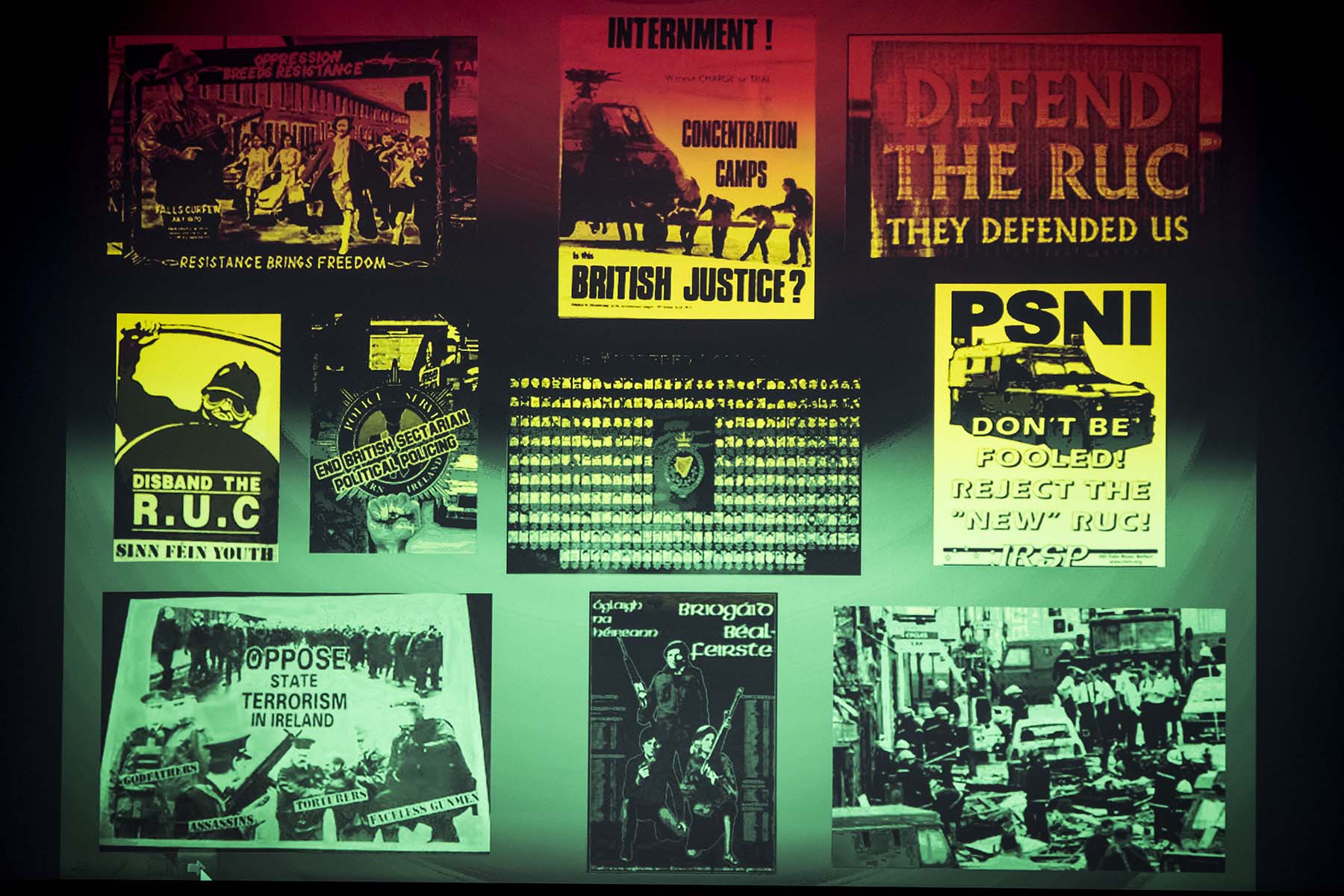

“I want to paint a picture of a society where the police were distrusted by a lot of people, almost 50 per cent of the population,” White said in his lecture. “I’ll share how we moved to a place where, in my view, we’re in a much better place – where we’re more representative, more accountable, and terrorism has been diminished to a great degree.”

Turning around a terrible situation

White took University of Guelph-Humber students back to a time in Northern Ireland’s history when the political conflicts manifested in near-constant violence and chaos, when bombings and gun battles were a mainstay in the news.

“I grew up in a very violent place,” said White, who also served in Iraq in the temporary rank of deputy chief constable while attached to the U.S.-led coalition.

Initially, White explained, the Northern Ireland government’s response to the issue was to militarize the situation, with British troops deployed alongside the RUC to restore order through what White called “draconian measures.” If anything, that heavy-handed response only seemed to make the situation worse.

In fact, White’s lecture focused on how it wasn’t until the RUC – which was eventually renamed the Police Service of Northern Ireland – was drastically reformed around the time of the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 that the relationship between the police and the public started to improve.

Changes included positive action policies to achieve a better gender balance and to better-represent the Catholic population within the police force, as well as a change in mindset that White said was crucial to turning around the organization.

“For me, community policing should be at the core of what we do,” he said. “Community policing is both the means and an end to creating a situation where the community trusts police and works with them.

“I’ve spent all my working life in one uniform or another. Good, effective policing has a role way beyond law enforcement. It’s not just about speeding or parking tickets or criminal behaviour. In a divided country where there’s conflict and terrorism, policing becomes either a target for people’s concerns and criticisms or it becomes a facilitator and an enabler of making things better.

“We had to get rid of the distrust. It took a long time, but community policing was the vision of success.”

Important lessons

For the University of Guelph-Humber students who attended the talk, it was valuable to gain unvarnished insight into the challenges of policing in a seemingly impossible setting, especially since White was so forthright with sharing missteps made along the way.

“I myself took away that it is OK to make mistakes, as long as we learn from them,” Alpha Phi Sigma Chapter President Dalton Beseau said. “No justice system or political system is ever perfect, and it is through the difficulties that we can work to develop a system that works for everyone.

“Additionally, while there may always be conflict in Northern Ireland and around the world, it is how we respond to this conflict that is important. We need to work with those directly involved and communicate with those individuals because when we communicate, we can resolve many of the world’s most difficult challenges.”